Equine Gastric Ulcer Syndrome is one of the better understood digestive issues that horses face. It’s increasingly common knowledge that:

- The majority of race and show horses suffer from ulcers

- Ulcers largely result from modern management practices (high-grain diets and no or restricted turn out for starters)

- The best way to avoid ulcers to increase turnout and feed a diet of primarily forage

The problem is that by focusing solely on equine gastric ulcer syndrome, we ignore the signs and symptoms that may instead be linked to colonic ulcers. Colonic ulcers are more difficult to diagnosis and to study, and as a result are often overlooked. But they can have a serious impact on a horse’s health, particularly when misdiagnosed and subjected to the common treatments for gastric ulcers.

The Horse recently published an article entitled “Ulcers for Life” that unfortunately perpetuates these ideas regarding equine ulcers.

Our VP of Veterinarian Medicine, Franklin Pellegrini, DVM,, who has done extensive research into equine ulcers, explains why it’s so important that we recognize the prevalence of colonic ulcers in horses and the issues associated with misdiagnosis.

Symptoms of Gastric and Colonic Ulcers

The article by Dr. Janice Holland in The Horse February issue continues to perpetuate the myth that many symptoms likely associated with colonic ulceration are due to gastric ulcers. If some of the proposed symptoms are treated with the “variety of medications” proposed (ranitidine, cimetidine, omeprazole) and the true cause is colonic ulceration, horses could be at risk of colic.

To explain potential symptoms of equine gastric ulcer syndrome (EGUS), Dr. Holland describes a horse with “a tendency to lie down”, one that “occasionally looks at his sides and appears uncomfortable” or one with “a mild bout of laminitis”, and later references diarrhea.

The fact is that these symptoms are much more likely to reflect a hindgut condition, such as colonic ulcers.

The challenge is that gastric ulceration often occurs simultaneously with colonic ulceration. Yet, because gastric ulcers are more widely understood than colonic ulcers, the symptoms are easily incorrectly associated with the gastric ulcers and not with colonic ulcers which may be present at the same time. While gastric ulcers are correlated with such symptoms, they are not causative, a position with which Dr. Nathaniel White agreed in our exchange shown in the January issue of The Horse.

Colonic Ulcers and Colic Risk

The risk of colic arises when products are used to shut off the production of acid in the stomach as a response to these symptoms, especially when the horse is fed a diet of processed grain-based feed.

The rationale for this is well-described in various peer-reviewed studies (all available in the SUCCEED Veterinary Center) that unfortunately have not been given their due publicity:

- It is well known that high grain diets and intermittent feeding are now common in equine husbandry. It is equally well understood that, when the non-structural carbohydrates in grain and processed feeds reach the hindgut, bacterial fermentation produces a higher level of lactic acid rather than conventional VFAs resulting from the fermentation of forage. This condition is known as hindgut acidosis. (Swyers et al. 2008).

- In vitro exposure of colonic mucosa to cecal contents incubated with starch resulted in increased paracellular permeability (Weiss et al. 2000).

- Mesenteric arterionecrosis occurs and can be induced via endotoxemia (Oikawa et al. 2006).

The vast majority of equine colics are idiopathic. It is entirely possible that grain-based feeding patterns are a primary culprit, leading first to hindgut acidosis, then colonic ulcers, then ultimately to colic.

If a horse is treated with a gastric acid inhibitor, and continues on a high-grain intermittent diet (which likely gave rise to these conditions), then undigested grain will reach the hindgut in even greater quantities, exacerbating acidosis and the attendant “bacterial inversion.” In turn, this is ever more likely to create the conditions leading to colic.

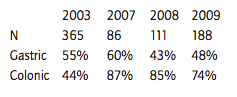

My own necroscopic analyses of over 700 horses, in four separate studies over a six year period, revealed the following incidences of ulceration:

This shows that the incidence of colonic ulceration in these studies is significant and growing.

It behooves all of us, especially veterinary practitioners, to be aware of the symptoms associated with hindgut and foregut problems and be able to differentiate the two. The consequences of misdiagnosis could be severe and need to be revealed to all.