Much like the decades-old The Price is Right’s sign-off — “don’t forget to get your pets spayed or neutered!” — horse vets across the world have issued a similar plea for years: “Don’t forget to deworm your horse!” And as horse owners and trainers, we’ve (mostly) listened, faithfully administering wormer at the appropriate times throughout the seasons, then figuring we’ve done what we need to do to keep the worms at bay.

But for a variety of reasons, we’re still losing the battle against parasites. The worms we’re targeting have changed, for one thing. Certain parasites have built up resistance, for another. And we have been treating horses by the herd, rather than taking an individualized approach to parasite control. For these reasons (and more), the American Association of Equine Practitioners (AAEP) published the first official set of guidelines for parasite control in 2014. This guideline has helped; publishing new recommendations for parasite control can, at very least, alert people that there’s a problem — but worms continue to wreak havoc on horses’ overall health. And one of the most serious results of a parasitic infestation is colitis.

The Connection Between Parasites and Colitis in Horses

Colitis is a term that simply describes inflammation of the lining (mucosa) of the large intestine, which frequently results in diarrhea and colic in horses. It’s important to remember that colitis is a symptom, reflecting the presence of inflammation, and not the disease that is the causative problem.

Colitis can be both chronic (a long-lasting condition) or acute (a short-term affliction). It can be caused by infectious, or noninfectious causes — including certain parasites.

The Effects of Colitis on a Horse’s Health

Severe colitis can result in death, due to tissue death, diarrhea, dehydration, compromised nutrition, hemorrhage, colic or toxic shock. Clearly, it’s not something to be messed with. And frustratingly, the underlying cause of colitis is often difficult to diagnose. However, we do know that several factors can predispose a horse to mucosal inflammation. Some are lifestyle-related, such as the increased stress brought on by competition, travel, or management conditions. Other cases have been tied to antibiotic use. Yet another reason a horse may be predisposed to colitis may be the presence of a parasite called small strongyles.

What are Small Strongyles?

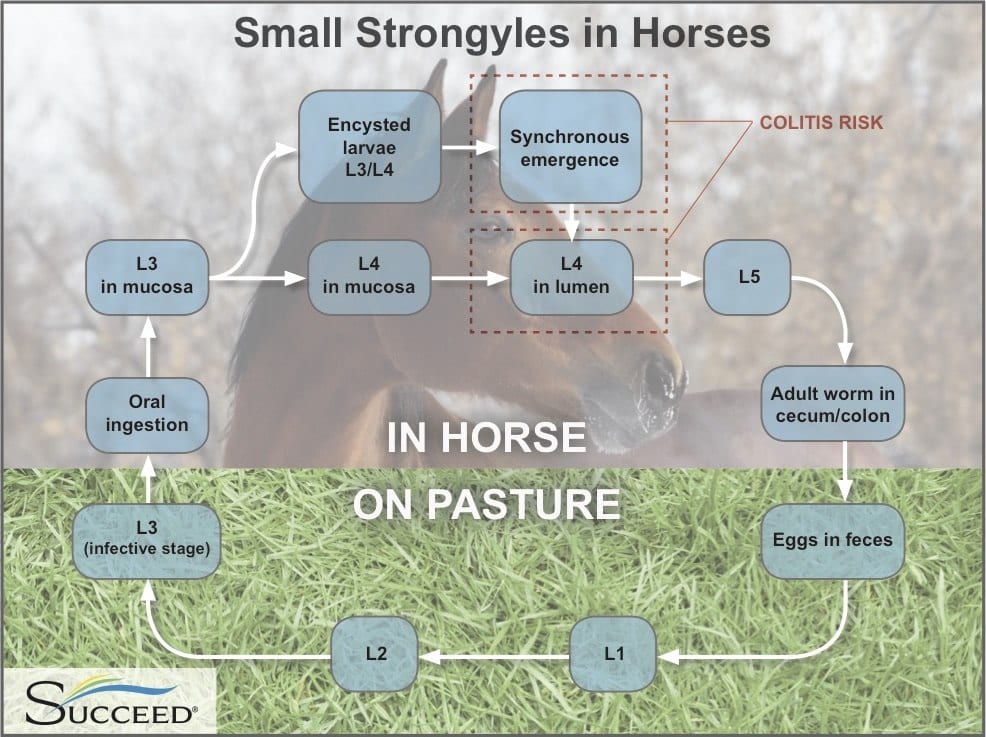

Small strongyles are also referred to as cyathostomes or cyathostomins. Unlike large strongyles, small strongyles don’t migrate through the body and internal organs of the horse, instead, small strongyle development simply takes place in the wall of the intestine. Here’s how it works:

- Horses picks up small strongyles out in the pasture. The pasture becomes contaminated with eggs when they are passed with the manure from an infected horse. The eggs turn to infectious larvae in the grass, and the horse eats the larvae.

- Once the larvae are ingested, they burrow into the wall of the large intestine and cecum, where they surround themselves with a protective, thick-walled cyst. The larvae remains in the protective cyst for a minimum of 2-3 months and up to three years. During this encysted stage, the larval worm is relatively safe from the dewormers you may routinely dose your horse with.

- When the environment is right, large numbers of encysted larvae can emerge simultaneously, migrating back to the lumen of the cecum and colon to continue developing into their final larval stage. Eventually, they will turn into egg-laying adults, and the cycle will start all over again.

The technical name for this group emergence of larvae from the intestinal wall is “larval cyathostominosis.” It is the time in the life cycle of the small strongyle when it is most dangerous to your horse, as the sudden emergence in large numbers can cause acute, and potentially fatal, colitis, or more specifically – parasitic colitis.

Note that small strongyle infection does not always cause parasitic colitis, but when it does it can be life threatening.

Symptoms of Parasitic Colitis

Unfortunately, parasitic colitis can be tricky to diagnose. But here are a few indicators that might tip off your vet to a case of parasitic colitis in your horse:

- The season is late winter or early spring, and your horse is under the age of six.

- Diarrhea is present. Diarrhea is a near-universal sign of intestinal inflammation, and one of the primary symptoms of small strongyles infection.

- Weight loss.

- Lethargy and debilitation.

- A low fecal egg count.

- Nutritional deficiencies.

- A delayed shedding of the winter coat.

- Episodes of colic.

The symptoms identified above will vary according to the stage the larvae are in; encysted larvae (stage 3 of the life cycle) are commonly linked with nutritional deficiencies, weight loss and a shaggy coat. Larvae in stage 4 (larval cyathostominosis) are typically linked with severe damage to the gut wall leading to sudden weight loss, diarrhea, and colic. Adult worms can cause lethargy, sudden weight loss, and debilitation.

Diagnosing Colitis Caused by Small Strongyles

Unfortunately, it can be challenging to pinpoint small strongyles as the cause of colitis. Because the inflammation of the mucosa occurs while the parasites are in larval stage (when they are not mature enough to produce eggs), a fecal egg count is generally not helpful. While strongyle eggs are not often seen on fecal examination, your vet may find gross observation of the sometimes white but typically bright red L4 or L5 larvae helpful.

How to Treat Parasitic Colitis in Horses

Like all cases of colitis, it’s imperative to commence treatment as soon as possible. When colitis is suspected, its treatment is somewhat similar regardless of specific cause, but it’s imperative to also treat the parasites causing the symptoms – the small strongyles – using the guidelines set out by the AAEP.

Standard colitis treatment typically includes:

- Anti-inflammatories to reduce bowel inflammation

- Intravenous fluids to correct fluid and electrolyte loss,

- Plasma transfusions for severe protein loss,

- Anti-endotoxin agents for endotoxemia,

- Analgesics for pain,

- Antidiarrheal agents,

- and nutritional support.

To treat the small strongyles infection, your vet will also likely prescribe anthelmintics such as:

- Benzimidazoles – e.g. fenbendazole and oxfendazole

- Macrocyclic lactones (ML) – e.g. ivermectin and moxidectin

- Tetrahydrophyrimidines – e.g. pyrantel salts

Unfortunately, the efficacy of any of these anthelmintics on small strongyle larvae is not high. While they are highly effective on adult small strongyles, the larvae responsible for causing colitis are well protected when they are encysted within the intestinal wall.

As a result of this, the outlook for a horse with parasitic colitis can be grim — but not entirely without hope. If you can rid your horse of the small strongyle infection, it’s possible to treat and help prevent future instances of colitis via intervention from your vet and a variety of management techniques, from increasing forage intake and reducing starch intake, to avoiding dehydration. It’s important to remember that rehabilitating and maintaining your horse’s digestive system is another key factor to help improve your horse’s chances at recovery.

Be sure that overall intestinal function is supported, and promote a healthy and stable hindgut environment for your horse. And of course, don’t forget to deworm your horse! But do so via the AAEP’s new guidelines for the best result — and to up your chances of avoiding parasitic colitis altogether.